Continuing last week’s debate, this article will seek to explore whether human reproduction is a product of evolution and what relationship that may have to cosmetic surgery procedures undergone by men and women. Basically, in this article I will consider the evidence in three phases:

- What is our evolutionary heritage from our primate ancestors, as deduced from our nearest primate relatives?

- What major evolutionary events separate us from our nearest primate relatives?

- How might we expect these evolutionary events to transform our pattern of reproduction and is that reflected in cosmetic surgery practices?

Sex Among the Primates

There is no uniform code of sexual conduct among our nearest primate relatives. Gorillas, chimpanzees, and bonobos all “do it” differently.

Gorillas are less closely related than the other two, but they provide an instructive contrast. Male gorillas maintain a harem, with a small group of tightly controlled females engaging sexually with a single dominant male. Competition among males for dominance is fierce, but generally final with males and their harems living isolated from other families. The consequence of this is that male gorillas have large, muscular bodies, while female gorillas are significantly smaller and with little sign of reproductive receptivity.

Chimpanzees and bonobos have similar but distinct reproductive patterns. In both species, females display receptiveness to reproduction with swelling of the genitals. Also in both species, females are generally promiscuous, although chimpanzees are more likely to have females who pair bond, although for short periods of time.

The Human Touch

Humans are distinctly different from our primate ancestors, from whom we are separated by three major evolutionary changes:

- Bipedalism

- Larger brains

- General hairlessness

How might these three changes have affected human reproductive patterns?

Bipedalism is the earliest evolutionary change that separates humans from other primates, occurring between five and six million years ago as the Australopithecines diverged from chimp and bonobo ancestors. Bipedalism could be expected to create many shifts in sexual selection. First, the presence of large, muscular buttocks, an inherent side effect of our walking stance, might have been read by ancestors accustomed to swellings that signaled reproductive receptiveness, as a sign of continual receptiveness.

This effect would have been most pronounced among our early ancestors who would have changed between a bipedal and quadrupedal stance, both increasing muscle mass while keeping the head down where the signal would be read.

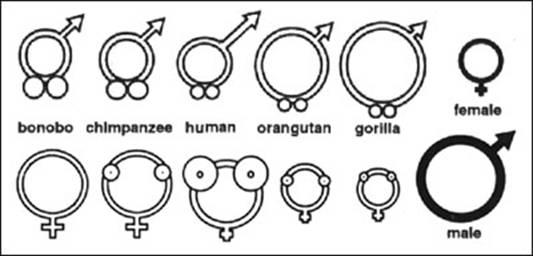

This pattern being established during the transition, the signal would be missed once our ancestors became fully bipedal, having less visual contact with the signal, thus leading to a desire, i.e. a sexual selection pressure in favor of some comparable signal more fully visible while standing. Enter the unusually large human female breasts. How unusually large? Consider this comparison among our closest primate relatives.

Source: Sexual Paradox by Christine Fielder and Chris King.

Note also the relatively large penis of the human male, which would also be selected for following bipedalism, which makes the penis highly visible. Once men stood upright sexual selection by females for a larger penis might be expected, although the role of the larger penis is probably related more to display in male-male dominance battles than sexuality.

We can also expect that bipedalism would promote signals from the facial area, leading to more selectivity with respect to facial structure and expressiveness.

Larger brain size seems to have been both a driver and a response to tool use among our early ancestors, which accelerated rapidly over other primates once our ancestors found themselves with free hands.

The larger brain size had an adverse side effect on human birth, already strained by the changes in the pelvic region caused by bipedalism. In order to counter the difficulties of passing the large-brained child through the vaginal opening past the pelvis, human females who had their children at a slightly earlier stage in fetal development would have had a higher survival rate, eventually leading to the current situation where humans give birth to a child whose brain is only 29% of adult size, compared with chimpanzees, who give birth to children whose brains are nearly 50% that of adult size.

The cost of early birth? Human children are more helpless at birth than any other animal, including marsupials. Anyone who has had a child knows what this means: months, even years of dedicated care. How could a woman possibly be expected to care for a child while leading the far-ranging life our ancestors must have led to spread by foot to every corner of the globe? She would need help. She might receive this help from other women, but our closest primate relatives jealously guard their offspring from the hands of other females, so this seems an unlikely source of aid for early humans. Where then might a woman seek help in caring for their child? In their mate.

Human males put a lot of resources into the rearing of their children, not only in terms of food and shelter, but time investment. But in order for a woman to be able to count on the man’s investment, the woman and the man must be bound tightly by bonds that are likely to last the five or six years necessary for a human child to be old enough to walk and socialize with a peer group for protection.

To foster this bond, humans developed a complex set of mating rituals for displaying pre-sex and post-sex emotional fondness. All cultures share this. Most of these rituals involve face-to-face communication, both verbally and nonverbally through looks and through kissing, and the touching of bare skin. Skin-to-skin contact became the medium through which humans began to develop what we now call “erotic love.” As an essential component of receptivity to erotic love, bare skin became a desirable quality in both males and females, creating a feedback loop of sexual selection, leading to the almost total loss of hair by members of both sexes.

Cosmetic Fallout

If this account of sexual selection in human evolution is true, we would expect that many people to try and present false indicators of a positive genetic heritage: i.e. they would want to look more beautiful in ways that had been sexually selected for during our evolutionary history. In other words, we would expect cosmetic surgery practices to center around three loci:

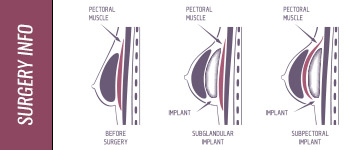

- The chest area to distinguish male and female sexual dimorphism;

- The face to enhance signals of health

- Hairlessness and healthy skin.

Let’s see if that’s the case.

According to statistics from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS), of the surgical procedures directed at a specific body region other than the face, 72% were directed at the chest area, led by breast augmentation and breast lifts for women and breast reduction in men. Over 58% of all cosmetic treatments were directed at the facial area, including blepharoplasty, facelifts, rhinoplasty, and a host of facial injections, especially BOTOX® cosmetic. Furthermore, the majority of other treatments are dedicated to managing hair and giving skin a healthy, youthful appearance through microdermabrasion, laser skin resurfacing, laser hair removal, and sclerotherapy.

So it seems that evolution has in fact affected human sexuality, which means that we are left with the mystery of why it is the females of our species and not the males who are so dedicated to ornamentation. Although one might argue that men invest heavily in children, the incredible toll that childbirth takes on a woman means that women invest still more, so why, then would women be so much more ornamented than men? We will investigate this question further in the next installment.