So what muscle are we talking about here? It’s the “pecs”, the pectoralis major and pectoralis minor. They’re attached to the chest wall, the pectoralis major being thicker and overlaying the pectoralis minor.

Under (i.e., behind) them, the chest wall is made of ribs and intercostal muscles (between the ribs), and it protects the heart, lungs and large blood vessels. The pecs also connect to some abdominal muscles via muscle fascia, which is a tough collagen sheet that covers and extends from the muscle strands. And they connect in the same way to the serratus muscles, at the sides of the breasts. And on the surface of all is the breast tissue, also called the mammary gland.

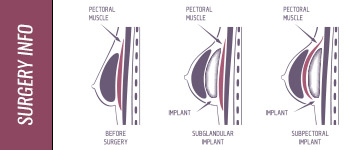

So there are three main layers of tissue on the chest: the chest wall, then the muscles, then the breast itself. With this in mind, we can picture how breast implants can be inserted:

- Sub-glandular – below the breast tissue but above the pectoral muscles (and if you think about it, all implants are “sub-glandular”, since they’re all below the breast tissue; but this term is used to refer to those that are above the pecs);

- Sub-pectoral – below the pectoralis major muscle and above the chest wall (also called retro-pectoral).

When the breast implant is sub-pectoral, it lacks strong support at its lower end, because it is placed there through a long incision below the breast and no muscle covers or supports its lower end. This incision cuts through the muscle fascia, leaving the implant fixed in place only from its top end.

So a third variation was developed, called

- Sub-muscular or Sub-fascial. This means the implant is below the breast tissue, below the pectoral muscles, and below the fascia that connect the pecs to the abdominal muscles and serratus muscles. In this position, it has a bra-like support from the fascia. To keep the fascia intact for this support job, the incision is made in the armpit.

Incisions in Breast Implant Surgery

There are three choices here, all of which will cause some scarring:

- Inframammary incision – at the base of the breast, near the chest wall; an inconspicuous scar

- Transaxillary incision – in the armpit; therefore no scar on the breast

- Periaerola incision – around the lower side of the aerola, that darkened tissue around the nipple. This is the most commonly-used incision. It leaves a small and discreet scar, but brings increased danger of damage to milk ducts or nerves related to milk let-down).

All positioning of the implants can be done using any of these incisions.

Some surgeons also use the TUBA (or trans-umbillcal) method that involves endoscopic surgery through the belly button. Click here for more information about the TUBA Breast Augmentation procedure and to compare the TUBA procedure with Trans-Axillary Breast Augmentation.

How the Breast Implant Procedure Works

After the incision is made, a tunnel or passageway is cut for inserting the breast implant to its final position. Then tissue and/or muscle is separated to create a pouch or pocket to enclose the implant, and much surgical skill is employed here to place the pocket so as to give the breast its best look after the implant is filled. This might even involve re-positioning the nipple and including breast lift surgery and the surgeon might use a temporary implant, called a sizer, which he’ll remove after he’s decided on the best placement.

Negative post-op developments

Here are the negative events that are most related to breast implant placement:

Bottoming out

The breast implant drops below the level of the breast tissue. This causes a bulge in the wrong place and makes any inframammary scars visible on the breast.

Rippling

Some doctors believe rippling, wrinkling on the skin, is caused by too large a pocket being created for the breast implant. However, most believe it to be caused when the breast implant settles into position in its pocket, after the post-op swelling goes down. It pulls on the scar tissue that develops around it in the pocket, which pulls on the skin, causing a rippling appearance.

Interference in mammograms

The breast implant may hide breast tissue, potentially cancerous tissue, thus giving a false mammogram result

Capsular Contracture

The scar tissue that forms around the breast implant contracts, squeezing the implant and causing hardening of the breast, along with discomfort or pain. This usually happens to some degree, but to what degree is the question. It can be corrected by further surgery, where that scar tissue is scraped out to make more space for the implant.

How do these negative developments relate to each implant positioning?

Although there is some disagreement among plastic surgeons, the following is largely agreed upon:

Sub-glandular

- Most often “bottoms out”

- Has the highest risk of rippling, especially if the implant is textured

- Most likely to interfere with mammograms

- Most risky for capsule contracture

Sub-pectoral

- Fairly often bottoms out

- Seldom leads to rippling

- Little interference with mammograms

- Medium risk for capsule contracture

Sub-muscular

- Seldom bottoms out

- Lowest risk of rippling

- Little interference with mammograms

- Lowest risk of capsule contracture

So the sub-muscular placement gives the best result. But it comes with a few of its own disadvantages. These are:

- It’s the most difficult to perform, so that not all surgeons are able to offer it

- It involves the most post-op discomfort and longest recovery time

- Some women who work out with weights say the muscle squeezes the implant, creating an unnatural shape

- The breast implant sits higher on the chest, since the pecs don’t tend to sag. So if the woman has some breast sag, there may be some disconnect of contour between the implant mound and her natural breast tissue. This can be corrected by adding breast lift surgery to the breast augmentation surgery.